Cyberhate – ‘It’s not coming out of ‘the internet’, it’s coming out of us.’

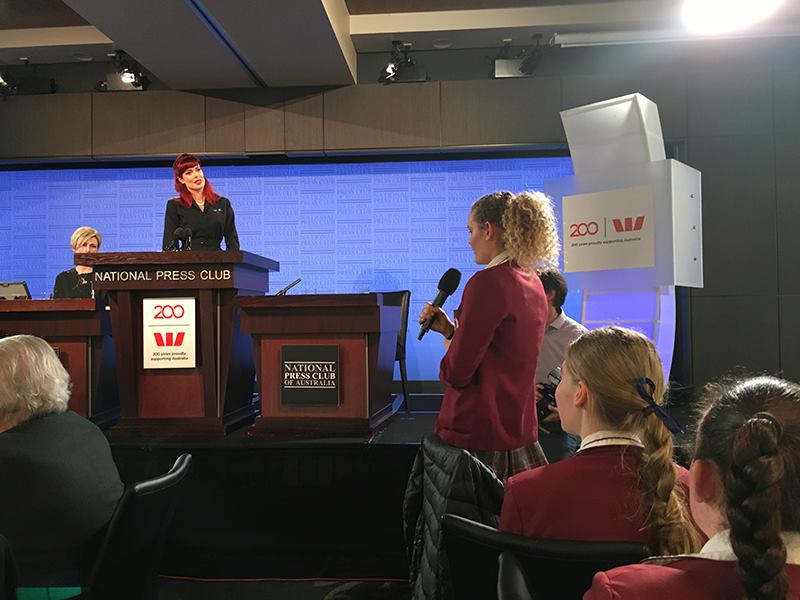

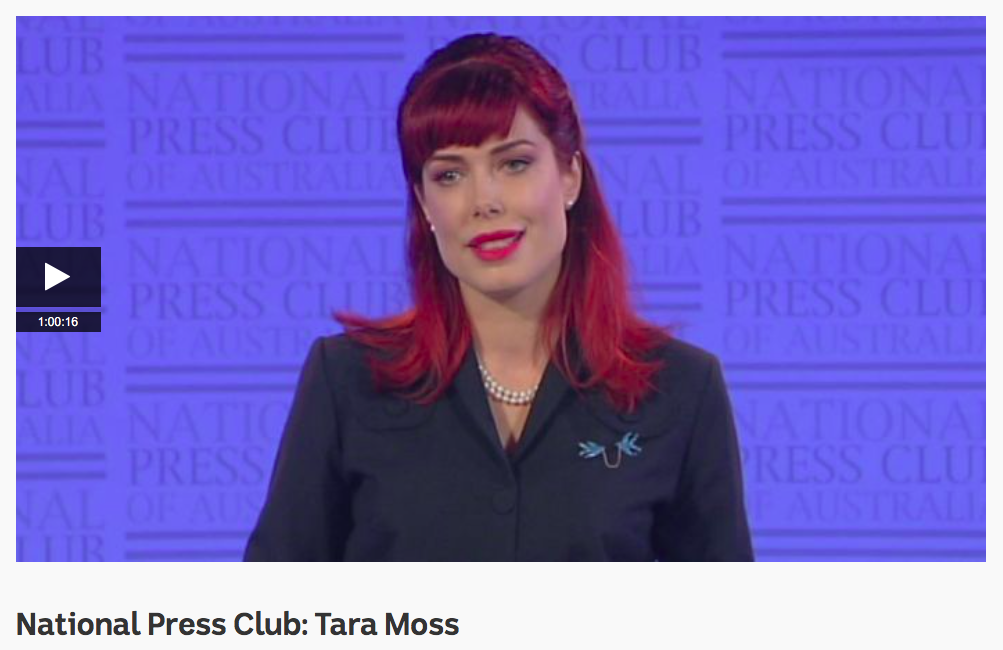

Last week I had the privilege of speaking at the National Press Club on the subject of cyberhate, or online abuse. My address, ‘Cyberhate and Beyond’ was televised and can be viewed here. My speech is transcribed below. For the full address including audience and press gallery questions, please watch the video at the link above. To watch my documentary on the subject, Cyberhate with Tara Moss, click here.

*

Thank you. I’d like to acknowledge the traditional owners of the Canberra region, the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people, and pay my respects to their elders past, present and emerging. I’d also like to make a special mention of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in Australia, and Indigenous women around the world who are so often the unsung heroines on the front lines of many of the issues I’ll be discussing.

Thank you to Women in Media and the National Press Club for the invitation to speak.

Last year Australia experienced a first, when a former Prime Minister publicly acknowledged that if women want to participate in public or political life they must expect almost daily rape and death threats (That was Julia Gillard, Oct 11, 2016). This wasn’t a scare tactic. To the contrary. This was an acknowledgement of the proliferation of cyberhate many women are already all too familiar with.

The prevalence of Cyberhate, or online abuse, has been recognised more openly in recent years. As online platforms and resources have become integrated into our daily professional and personal lives, particularly over the past 15 years, this has come with great benefits and for many, and increased opportunities, but also abuse.

ACMA estimates that 91% of Australians use the internet. The latest Sensis Report estimates that the majority of Australians – 79% – also use social media, making those spaces powerful connectors and an extension of social and professional Australian communities and global communities.

When people are abused online, however, Pew research suggests between 19% and 23% of people take some action that diminishes their own online presence. They delete an online profile, withdraw from online forums, and more. In addition, 9% even stop attending certain offline events or places. Likewise, 27% report that they decided not to post something online after witnessing the harassment of others.

According to the Data & Society Research Institute and the Center for Innovative Public Research young women are the demographic most likely to self-censor specifically to avoid online harassment, with 41% of women ages 15 to 29 self-censoring to avoid abuse.

All this – self-censoring and diminishing ones public presence – fits with the common narrative that tells victims of online abuse and harassment to stop being abused. The way they should do this, apparently, is not to speak out, or simply not to be online and participate in public life. Many women and girls, for example, have often been told to ‘just switch off’.

So how bad is online abuse, or Cyberhate, today? Because of the relative newness of the technology used, there are a relatively slim number of long-term, large scale research studies to draw on, and what’s there is hard to cross reference as many studies and surveys use wildly different definitions of abuse.

What we do know is that people of all genders and occupations receive online abuse, including an estimated three quarters of Australians under 30 and about half of people of all ages. However, I must stress that online abuse is not homogeneous. Just because it happens online, or using digital technology doesn’t make what happens the same. The motivations, the behaviours themselves, the severity and the impacts vary enormously.

In fact, the expression ‘online abuse’ is almost as broad as the term ‘offline abuse’, if we employed such a term to apply to physical world behaviours. It isn’t possible to cover all those variables in just 30 minutes today.

I will have to narrow my focus to a particular demographic in order to give an example of the impacts of online abuse, but as abuse occurs across demographics, I want to use my talk today as only one example of a multifaceted phenomenon within a bigger picture.

My beginnings online

Before I go further here, I should probably confess that I love the web. It’s benefited me.

The weblog, or blogging, was developed in the 90s, but it didn’t come into my life until 2009 when the ABC asked me to blog the Sydney Writers’ Festival. I’d written five novels at that stage but hadn’t ventured into online publishing. Not too long after that ABC blog, I began with my own blog The Book Post, which seemed a suitable focus as a novelist, and I slowly began to integrate blogging and social media into my professional and personal life. I later expanded my posts to become more politically engaged, however. With more political engagement, particularly about human rights, equal opportunity and women’s rights, came abuse.

Prior to say 2011, I don’t particularly recall receiving abuse online. That seems almost quaint now.

But there is a reason I am still online 8 years later, blogging, and posting across social media platforms, and now even with a make do and mend Youtube channel, Sewing Vintage, about sewing and fixing clothes rather than disposing of them – a focus that I think has always had value, but perhaps holds particular value in an age where the fashion industry is now reportedly the second most polluting industry in the world behind oil.

With online publishing – and that’s what so much of this is – you can create content of interest to an audience, on a topic that may be unlikely to be found on commercial TV or in your local, traditional media broadsheet. Blogging, vlogging, alternative media and social media have equipped many individuals, ideas and causes with a voice. One significant benefit for me, has been that prior to blogging and social media, everything the public knew about me was mediated through others, and that often resulted in stereotyped portrayals – opportunities to communicate directly with the public have allowed me to break through much of that.

The internet is powerful. Among other benefits, women, and other groups who are not well represented in mainstream traditional media can tell their stories in their own words, publish their work and have their voices amplified online without first gaining the backing of the traditional or commercial media gatekeepers.

Why might that matter? According to the 2015 GMMP Who Makes The News report, worldwide, fewer than 1 out of every 4 people we hear from or about in the media is female. That was just 17% in 1995 and we haven’t even climbed 10 percentage points in 20 years. It’s been stuck at 24% since 2010. The power players in Australian media are gradually changing of course, but OF the list of signatories to the Joint Media Statement on media law reform this year, 25 were men and only 3 were women. Most influential forums show similar issues.

Last year by my calculations just 24% of National Press Club speakers were female, for example. (And of course that looks similar to the representation of women in cabinet.)

There is some action on this, but traditional media has been and continues to be male dominated, no matter how you measure it. Women’s Leadership Institute Australia put out a report last year that showed just 21% of quoted news sources in Australia were female. The same report showed that just 28% of opinion editorials were authored by women. I could go on.

The point is, with all this in mind, there is nothing mysterious about the eagerness with which women have embraced alternative media. It also means these alternative ways of speaking out may have particular value for women and others, whose stories, opinions and reporting are not as broadly heard via traditional channels.

Above: Tara Moss addresses the nation at the National Press Club. Photographs by Karleen Minney.

Abuse

Last year I began work as co-executive producer, co-writer and host of the documentary Cyberhate for the ABC. There were plenty of reasons for me to pitch a documentary on the topic, which I’d also written about in my 11th book, Speaking Out.

You see, although people of all gender receive online abuse, women and girls have been increasingly identified as strong targets of online abuse, particularly in terms of death and rape threats, sexual harassment, image-based abuse, stalking and more.

I’m no stranger to some of that.

One powerful illustration of how this phenomenon manifests in media can be found in the large-scale research conducted last year by the Guardian. They examined 70 million comments over 10 years and found that articles written by women received more abusive comments across almost all sections of their publication than those written by men, and that of the ten regular writers who received the most abuse, 8 out of the 10 were women. Also of note is the fact that the two men were people of colour, as were 4 of those women. So racism and also persistent sexism are alive and well today, online and elsewhere, in addition to homophobia, transphobia, ableism and more.

For many women, copping cyberhate – including personal threats and graphic sexual harassment – has become a part of their job. Dealing with it has become a daily unpaid labour of banning, blocking, reporting and in some cases regular reports to police, as well as other considerations for managing personal safety – protecting the identity of vulnerable kids and family members, moving house, moving state, and more.

Abuse can be extreme. Video Game designer Zoe Quinn’s life was turned upside down by a sustained campaign of online abuse, rape and death threats, and doxing. “If I ever see you are doing a panel at an event I am going to, I will literally kill you,” read one of many thousands of messages aimed to silence, intimidate, and push her out of her professional work.

Her Wikipedia page was changed at one point to say she was going to die “soon.” She said at the time: “How could I go back to my home? I have people online bragging about putting dead animals through my mailbox. I’ve got someone in California who I’ve never talked to, hiring a private investigator to stalk me. What am I going to do – go home and just wait until someone makes good on their threats?”

During the filming of Cyberhate I spoke with numerous recipients of abuse across all genders and across the political spectrum, many of whom receive regular death threats. Australian Greens MP Mehreen Faruqui, for example, is bombarded with regular, racially charged threats, with descriptions of how she should be or will be killed. She explained that there are messages she can’t even share with her husband, they are too disturbing.

Another person I interviewed who’d received multiple death threats was conservative commentator Andrew Bolt, who described Twitter as a ‘sewer’.

A sewer?

He’s right of course. He’s also wrong. You see, there are a lot of serious downsides to what happens online, perhaps especially on social media, and I’m one of many people speaking out about that, but completely writing off the up sides is a whole lot easier when you may not technically require them.

You may not need the added opportunities for social connections when you have powerful friends – political and media heavyweights, for example. You may not need the opportunity to be heard via alternative media when you have a weekly newspaper column and blog, a co-presenter role on a syndicated radio program, and your own TV show each weeknight.

From that kind of traditional media position, yes, Twitter and the like could be seen as unnecessary at best. I understand that view.

But for some of the other people I interviewed for the documentary, notably many of the women and people of colour, Twitter or other social media outlets offered significant opportunities – opportunities they hadn’t received elsewhere. Often it was online where their writing was first noticed, where they made valuable connections or first developed a loyal following.

Perhaps fittingly, a sewer is defined as a ‘underground conduit’ and if you’ll indulge me in a slightly clumsy comparison here, there has been a quality of the underground about Twitter since its inception in 2006.

This is now complicated by commercial interests, as that underground becomes decidedly more mainstream and corporate, and now even a US President uses the medium to make ‘official statements’ or to attack detractors, but compared with traditional media forms, social media is a place of relative complexity, dissenting voices and different views. The views of the marginalised and the powerful.

Twitter in particular has been a place for feminist activism. For the Black Lives Matter movement. The Arab Spring. For movements against ableism, transphobia, homophobia, racism. A speaker on these issues won’t often have the opportunity to express their views on a national TV show, let alone 5 nights a week.

But as I said, he was also right.

Social media, including but by no means only Twitter, has become notorious as a mechanism for directly abusing people, sometimes simply with nasty commentary, which is all part of life and free speech, but also increasingly, with death and rape threats, and targeted, organised campaigns of harassment.

Online abuse can quickly grow in scale.

I recall one afternoon when users were tagging each other, creating a group to fill my feed with harassment. I’m pretty lucky online, most people are fairly civil, and I was confident this particular group of abusive individuals would grow bored and find another target in due course, so after blocking and muting and seeing more of it pour in, I switched off.

Then around 10pm I got a notification from my friend Benjamin Law.

He was contacting me because a Faux Tara Moss Twitter account was tweeting graphic content about rape and abortion directly to QandA, during the show, claiming to be me. I had no doubt it was the same people. I’d logged off but they’d found a way to get my attention. Blocking and muting wasn’t enough. Logging off wasn’t enough. I had to log in again, see the abuse, snapshot it, report it and wait.

In 2015 when doing unpaid work in advocacy against sexual violence I experienced a spike in online threats of a violent, sexual nature. One man wrote incitements to rape me, which I won’t repeat here. His Twitter feed was filled with violent hardcore pornography, photographs of women with their mouths being covered by men’s hands, pictures of high-profile women with the word “rape” and an image of US news anchor Megyn Kelly’s face Photoshopped onto a naked woman engaged in sex. I reported the account to Twitter, who contacted him and asked him to “discontinue this behaviour”. Surprise surprise, this prompted more abuse.

Twitter made it clear in that case that the onus was on me to report him again if the behaviour continued, but of course in order to do that, I’d have to unblock him, expose myself to more abuse, and record it.

I’ll be honest, I don’t usually have time to do that. I have a family to support. I have a life.

But this time, I did it. It took further communications over four days, with yet more screen shots and URLs as evidence, to point out what was obvious in the first place – he was using Twitter almost exclusively for abusive purposes, against its terms and conditions.

As I wrote to Twitter at the time, “I hope you will agree that allowing a user to continue in this way makes a mockery of Twitter’s rules and new complaint procedures.” The account was finally suspended. Of course he could start another account up in minutes.

Compared to that experience, Twitter’s response to the fake Tara Moss account was incredibly swift and professional. It took under 30 minutes to take it down once I was alerted. Responses from online platforms vary enormously, in my experience. So do their interpretations of their own policies and rules of service. For people who have to report abuse regularly, these inconsistencies are very familiar.

Threats and harms, unpaid labour and more

These two examples hardly scratch the surface, but perhaps give some taste of the unpaid labour that would be involved in being the regular recipient of such abuse. Now imagine that abuse involves breaches of privacy, public incitements to attack you in your home, your place of work, in the street or during a public appearance. When we claim that online abuse is ‘just words’, we are being naïve, or perhaps even deliberately dismissing experiences that are not our own, and the testimony of people – particularly women, young people, marginalised people – we don’t take seriously.

There are a spectrum of behaviours online, most positive, but some extremely dangerous.

As for the psychological impacts of abuse, there are plenty of studies now showing links between sustained emotional abuse and mental illness. And for the documentary Cyberhate I underwent an MRI while exposed to online abuse I’d received, and the scientists in the room measured increased heart rate and stress responses, all of which are unsurprising. We are human after all. We have, for good reason, developed strong physiological responses to threats.

I can’t illustrate the true spectrum of online abuse to you today because my speech cannot contain strong language. I also can’t show you images – it’s not only words. But I can tell you that research by UNSW academic Dr Emma Jane into gendered cyberhate shows that targets of this kind of abuse endure “many layers of suffering” and can include victims contemplating, threatening, or attempting suicide, career derailment, financial losses, long-term psychological impacts, and real-life bodily harm.

And you only need to see the specific manifestations of abuse to know that this is not coming out of an abyss, it’s not coming out of ‘the internet’, is it coming out of us. As a culture we are pouring our prejudices into the technology we use.

‘This is not coming out of an abyss, it’s not coming out of ‘the internet’, is it coming out of us. As a culture we are pouring our prejudices into the technology we use.’

For example, beneath a QandA news clip of my showing solidarity with survivors of sexual assault, there are the usual comments about my being ‘a whore’.

Standard for any woman who has experienced such a violation. Again, this is not coming from ‘the internet’, it’s coming from people using the technology of the internet. And it’s both common and familiar.

Since Cyberhate, some online abusers – I don’t like the word ‘troll’ – have spent a bit more time on their efforts, and the iconography is often curiously phallic. One Youtube account copied material from the show, and simply had a cartoon penis illustrated – how can one put this politely – faux ejaculating on me, on Van Badham, on the late Charlotte Dawson. Not on the men interviewed for the show, interestingly. As amusing as this grade school cartoonish-ness may be for some, it’s not happening in a bubble. It is an illustrated version of a similar form of harassment played out using images of unsuspecting women without their consent, experienced sometimes on a very large scale by various female journalists and public figures. And it is a rare young woman online today who has yet to receive unsolicited images of erect male genitals from strangers. There is no warning that precedes sexual harassment like this. It just arrives while you are posting about Syria or conversing with a reader.

I have sometimes wondered what cultural shifts would be necessary, what historical plots and laws and timelines altered over the past few centuries, to provide a culture in which the genders were flipped, and women persistently sent images of their sexual organs to men without consent, in an attempt to dominate, shame and bully them.

For the many people who regularly receive this kind of harassment, often but not always women – whether it be death threats, rape threats, racially charged abuse, fat-shaming or graphic sexual harassment – it’s as if they are running the same race as the rest of us, the same race as their colleagues, to be heard and to establish themselves in the world, create careers and financial stability, they’re just doing it in a violent head wind.

This is particularly true for marginalised women, those who are economically disadvantaged, or who are the target of discrimination because they are disabled, or queer, or trans, or people of colour, or because they look different. The discriminations that exist in the physical world exist online because it is the same world. And those forms of discrimination stack up. They intersect. They influence opportunity and how much support and safety a person experiences when this stuff happens to them.

The technology is different. The abuses are essentially the same.

This isn’t to argue that things are as they always have been, however. To the contrary. These technologies are relatively new tools and brings up fresh challenges. And this is where we need to make up some ground.

What does the future hold?

One thing is for certain: We can’t keep doing the same thing and expect to get a different result.

There is not going to be a single, cure-all for the multi-faceted forms of online abuse we see today. But a cultural shift that sees this abuse for what it is, is an important start. And this is eerily familiar territory. Sexual harassment and intimate partner violence were culturally considered inevitable and acceptable, and for centuries were not acted on as a result. It’s taken a lot to shift those attitudes.

Interestingly, anonymity is no longer a prerequisite for online abuse, if it ever truly was. As time has gone on, more people appear to have become comfortable participating in it. It’s been normalised.

At the moment there is a lot of focus on online safety and I support much of what you could call ‘Victim Prevention’, but I’d also like to see a focus on ‘Perpetrator Prevention’. Rather than simply telling the targets of the abuse, again and again, what they need to do to be abused less or have fewer crimes committed against them, we should be clear about what our rights are online and what constitutes abusive and illegal activity.

Yes, we can debate, criticise and even be unpleasant. But rape and death threats aren’t part of debate.

That should be clear, and from the questions I get literally every week from adults and school kids alike, it seems it is not.

We can look more seriously at online ethics, in schools, yes, but also among adults. We can’t continue the myth that only kids are doing this stuff. That’s simply untrue.

We can be clear about how to spot abusive online content and report it rather than participating in it, rather than sharing material that is clearly obtained without consent. We can stop condoning abuse as silent bystanders. And certainly we can stop telling victims of consistent, sometimes highly organised and targeted abuse that they should log off – that abusers have more right to these public spaces than they do.

Why do people threaten women in public life with rape and death? Because threats of rape, as well as rape itself has been used to intimidate women for millennia. And in the case of online abusers, they’ve got the message loud and clear that they can do this, because it’s ‘just what happens’.

But there are good people at work trying to change this. At a Symposium on Cyberhate this month I had the privilege of workshopping the issues with a group of NSW police officers.

There were promising ideas from other experts on how to utilise technology, law reform and activism to counter extreme online abuse and to lessen its harms, but our group was tasked with acknowledging the fact that the current police frontline response to reports of abuse can be inconsistent, and some victims of serious online crime are still told to just ‘switch off’. This means some victims lose confidence in police responses and it also means that online crimes are not always recorded and valuable data is lost. On the other hand, many officers understood the issues and were doing their best with limited resources.

One idea that emerged came from NSW Senior Sergeant Nightingale, who suggested that perhaps a Cyber Crime pack, similar to the DV pack now given to officers could cut through some of the inconsistencies. While the current system generally involves an officer writing in their notebook, and that info being entered later into a computer, if it was recorded directly into a device one step would be removed, and the officer could be prompted through the correct steps to make sure all the right questions are asked. Even an officer that didn’t have experience with the internet could respond and record complaints in a consistent way and valuable data would be recorded.

How many Australians are being cyberstalked? How many are being doxxed – that is having sensitive personal information posted online for malicious purposes. How many Australians are experiencing image-based abuse, colloquially known as ‘revenge porn’ – a terrible term that implies the victim somehow deserved it.

With better, more specific, large scale data, we could better address what is happening out there.

This holds true for our research and reporting. Not all online abuse is the same and it can’t simply be recorded under one category that would see a single insulting message tick the same box on a survey as being the victim of a sustained campaign of cyberhate.

Human rights, public participation and democracy

Make no mistake: The aim of many online abusers is to remove their victims from the public discourse. Ginger Gorman, a journalist who has researched online abuse extensively speaks of one self-identified troll who targets people with autism and mental illness, who are recently bereaved, or who are women, and points out that he wants his targets to feel unsafe: “Sometimes I just do it to get them to, like, quit the internet.” he says.

No person of any gender should have to choose between participating in public life and activities online, and personal safety.

When we truly accept that the online world is part of our world, a digital technology that connects human beings, not its own universe, we can begin to more accurately apprehend that these threats on people’s lives and safety are an attack on human rights, the right to public participation, and participation in the democratic process.

I won’t accept that women in public life should expect almost daily rape and death threats. No one should have to. To combat that reality we must first acknowledge that what is happening is real, and it has real impacts.

Thank you.

Above: Tara is asked a question by Radford College student Georgie Sayers during question time.

Tara, I found your talk on The National Press Club, a very interesting topic. I have notice how Face book has changed, I have seen some very hateful comments made on this platform. So I was so heartened to hear the young school girl talk about the way Yassmin Abdel Magied has been treated. Paul Keating made comments about Anzac Day and there was not the same reaction. I would have liked to have been able to support her. There were such hateful comments on FB I decided best not to get involved. I do think people are not taught to debate issue. They become personal and stray from the issue. I remember a friend saying her husband studied some subjects in psychology and you learn how to present and a debate. When he worked at the CSRIO his comment was the Scientist has never been taught how to present an argument or debate. May be this is something we can teach in schools.

Hi Tara,

My respects to you.

As you rightly point out, the online world is not a world unto itself. It has become an invaluable form of infrastructure that mediates public (therefore: political) discourse. And like any other form of infrastructure, a debate rages on as to the extent to which it should be regulated and exploited, publicly owned or privatised.

There are two core problems with regard to the Web, of which cyberhate is but one nasty, chronic, inflammatory symptom.

Firstly, as you also point out, it’s some of the people, most of the time. With the anonymity it is perceived to provide, the Web has done us a bitterly ironic service. Barring some post-apocalyptic free-for-all, we’re probably not going to get a better chance of finding a representative sample that can help us determine exactly what proportion of people are – deep down – sadistic bastards. (Not in my most bitter, rage-filled moments have I wished on anyone the sort of stuff these wretches routinely send their intended victims.) Most of them would have to be what I call ‘timid sociopaths’ – attackers of opportunity, inflicters of pain too afraid to show their true colours unless assured of either their anonymity or a trump card of institutionalised unassailability. Only the thin veneer of civilised life stands between them and those of a sweeter nature as they walk past each other in the street staring at their mobile devices.

Secondly, speaking of sociopathic behaviour, we have the social networking platforms – the culmination of Web 1.0 and Web 2.0, and now Web 3.0, with its goal of making our every datum readable by artificial intelligences built by multinational corporations and government agencies to triangulate our every whim and intent. That is one of many reasons why, in not using the major platforms currently on offer, I consider myself to be, not a Luddite in rejecting these technologies, but an Anti-Luddite – being of the opinion that they are simply not good enough to bother with, and their providers too suspect in their intent. They’re just too primitive in terms of what they are offering us human beings – as a medium of communication, as a reliable moderator of behaviour, and as an extension or outsourcing of our higher cognitive functions. As it stands, online social networks have just turned the world into one big high school, with its status-conscious gossip, petty vanities, popularity contests, bullying and cruel ostracism. I doubt that anyone could seriously claim that the overall quality or maturity of our communication with each other has improved, even if its quantity, range, convenience, and contagiousness has.

Having watched the early-adopters volunteer themselves as guinea pigs, I decided quite a while ago that we need something a lot better. But that’s going to require a great many of us – you and me included – to suspend certain of our prejudices that aren’t nearly as self-evident as the repugnant examples we see in cyberhate.

Good afternoon Tara

My friend Bruce Whiteside directed me to the video of your speech at the Australian Press Club.

I was so impressed with both the content and your delivery.

Like Bruce, I’m unable at this time to share details with you about an ongoing ‘matter’ that involves us both.

However I want to state that it is clear that there is need for control of obscene, vicious and threatening Australian online content, and for enforcement of the existing Carriage of Menace legislation, and not just for Nova Peris or Troy Grant.

I’d contacted many authorities about Australian cyber abuse, including Mitch Fifield, Minister for Communication, whose office response was to refer me to an agency dealing with children’s online issues.

I’m writing to you now with an illustration of the kind of cyber abuse prevalent on what is self-described as an Australian political site.

These online comments are directed at a woman with whom I’m in contact, whom the attackers believe to be posting on Pickering Post as ‘Flysa’. This is under today’s article on ‘The kid…’

Stoney##22 30 August 2017 5:36:16 am

Hey fly shit…i figure out your problem and why

You got your taint torn in Hay Street brothels and you thought you were getting screwed in the twat but was really up the arse.

Appalling as this comment is, the one that follows is even worse.

I know the victim of this cyber abuse has many times contacted Larry Pickering to remove this kind of contact, but I haven’t noted any removal of this or similar material.

There has always been an element of Bar-room Boys Club commentary on this site, but this unmoderated comment plumbs new depths.

As you would be aware, local police find this kind of offense beyond their experience or ability to manage.

I’ve begun to despair that young female children will grow up in a world that accepts such filth and abuse directed at women as being normal.

It must be stopped.

Yours sincerely,